A great day at the races is virtually impossible without impassioned volunteers. At Everlong, our volunteers — friends, family, neighbors, former strangers — have covered all levels of experience and all measures of personality.

We cannot thank them enough.

A few of our volunteers have been not only new to volunteering, but trail running in general. And that’s great! Volunteering, aside from simply making you feel wonderful, is a great point-of-entry to the trail running community. We’re thrilled when a first-time volunteer joins us for a day on the trail.

To help new (and seasoned) volunteers feel as comfortable as possible in their duties, we assembled this guide. We tried to make it as general as possible so that it’s applicable to just about any trail running event.

Of course, every event has its own rules, wrinkles and idiosyncrasies. We’d ask you to please consider a different perspective when we offer guidance that may run counter to what you’ve experienced in the past. If, however, you think something is downright wrong or missing, please let us know. There’s always room for improvement.

The Quicksilver Running Club, managers of the Duncan Canyon aid station at Western States. Photo credit.

If you’re brand-new to volunteering, we suggest reading the guide in its entirety. It’s a 15- to 20-minute read and pairs nicely with an IPA. For those in a rush, we’ve linked to specific sections below. Click and jump!

OKAY, YOU’VE CONVINCED ME. HOW DO I SIGN UP?

WHAT IF SOMETHING ELSE COMES UP?

HOW WILL I FIT INTO THE OVERALL EVENT?

HOW WILL I KNOW IF I’M DOING A “GOOD” JOB?

WHAT WILL RUNNERS EXPECT FROM VOLUNTEERS?

IT CAN’T BE THAT SIMPLE. WON’T RUNNERS HAVE QUESTIONS?

HOW DO I SET UP AN AID STATION?

Why should I volunteer?

Before we jump into the nuts and bolts of volunteering, it’s worth highlighting a few reasons why you might forfeit a Saturday to make 183 PB&Js. While this list isn’t exhaustive, it covers most of the reasons we encounter and espouse — in no particular order, of course.

It’s a race requirement.

More and more races are requiring participants to volunteer in some capacity. This could be through trail stewardship work or spending some number of hours volunteering at another event. We fully support this practice and the many ancillary benefits it accrues to the broader trail community. While we don’t require volunteering for our shorter distance races, we still donate a portion of race registrations to local trail stewardship organizations.

Pro tip: if you’re volunteering for a race requirement and need the RD to sign a form, try to approach the RD or Volunteer Coordinator after your shift or the event is over. Chances are they want to truly thank you, and they may not have the bandwidth to do so in the middle of the action. Oh, and don’t forget your form at home!

It’s a great way to learn about trail running.

I dare you to volunteer at an aid station and not feel inspired and curious. If you’ve been thinking about your first trail run, or going up in a distance, volunteering provides a genuine sneak preview. Also, you’ll likely volunteer alongside folks who have run ultras and are happy to share their wisdom and showcase their wounds.

Pro tip: the wounds are exaggerated.

It’s fun and uniquely rewarding.

Volunteering is crazy fun and, perhaps more importantly, uniquely rewarding. You’ll receive countless thank yous throughout the day, and not one will be perfunctory. Runners fully appreciate that their success is linked to you.

My friend asked me to.

An ultra-marathon can be a deeply personal endeavor, but it’s an experience that many runners want to share with their friends. Quite naturally, though, not all these friends want to run for ten hours. Instead, they can share in the endeavor by making those PB&Js we talked about earlier and, later, drinking beer at the finish line.

Okay, you’ve convinced me. How do I sign up?

Signing up to be a volunteer is the easy part! Nowadays, most race organizers provide a “volunteer” form on their website or UltraSignup page. We, for example, have a volunteer registration form right here. The great folks at Rainshadow Running include a button on UltraSignup.

Most forms will ask for basic information — name, email, phone, etc. Some may ask you to provide a preferred assignment or level of experience. This additional information is used to assemble the best possible volunteer teams — for example, pairing a seasoned volunteer with a newbie — and make sure volunteers are fully satisfied in their roles. To be clear, this information is not used to screen volunteers!

You should have no problem bragging about your volunteering skills. As a RD, I would LOVE to know if a volunteer has experience operating a race clock or collecting bib numbers at an aid station. We want to know all about you.

Once you’ve signed up, you should expect to hear from some member of the race management team within a few weeks of the event. If the race is months away, you might not hear anything for, well, months. That’s okay. A communication will arrive in some form, and will likely provide timelines, responsibilities, expectations and introductions. Alternatively, the communication may be an invitation to a volunteer meeting, which many race organizers view as an effective means of sharing information and, more importantly, inviting ideas and questions. We highly recommend attending these meetings, when offered.

If you’re uncomfortable with the assignment you should raise your hand right away. If you can’t swim, like me, you probably shouldn’t volunteer at Rucky Chucky. Again, race organizers want all their volunteers to be happy from start to finish.

What if something else comes up?

Most 100-milers have waitlists because a meaningful number of runners drop from the event as race day approaches. This could be due to a variety of perfectly good reasons: injury, illness, a shift in priorities. One of my best friends found out she was pregnant — and dropped from a race that shared her son’s eventual birthday.

If runners can change their mind, so, too, can volunteers. Shit happens. The critical thing to do is communicate your change-of-mind as early as possible. The more time race organizers have to cover your responsibility set, the better. Insofar as it’s possible, please do not pull a no-show.

Finally, it can’t hurt to offer to volunteer at a subsequent event: “Hey, I’m incredibly sorry I can’t make it to [event A]. I didn’t think my friend would ask me to give a speech. If it’s okay with you, I’d love to volunteer at [event B]. I’ll be available all-day Friday and Saturday.”

How will I fit into the overall event?

The first thing a volunteer should know: you will rarely, if ever, be alone. Trail running is community-driven from start to finish. Even if you’re a sweeper at a low-key event (more on sweeping below), you’ll likely have back-of-the-pack runners to keep you company.

To understand this group dynamic, consider the total number of participants — runners and volunteers — at UTMB. UTMB’s website offers the following narrative: “…we are more or less 2,300 people sharing the same dream carefully prepared over many months. Despite the incredible difficulty, we feel serene thanks to the help and comfort offered with by 2,000 volunteers…” These are not just words. I ran UTMB in 2016 and, had I not read this passage, would have thought the ratio of volunteers to runners was 2:1.

While UTMB is the largest ultra-length trail running event in the world, its volunteer-to-runner ratio reflects the norm. Generally speaking, 100-milers have a 1:1 ratio. (Western States boasts a whopping 1,600 volunteers for 369 runners!)

At races of shorter distances, like a 50K, the ratio is probably lower — perhaps one volunteer for every three runners. This is because volunteers can more easily wear multiple hats, and runners just don’t need as much help. Nevertheless, at a 50K of 60 runners, you should still expect to be one of 20 volunteers. Like I said, community-driven.

The overall volunteer team is further broken down into subgroups by assignment. The most obvious example is an aid station. If you choose this volunteering assignment, you’ll find yourself spending 8+ hours alongside the same 2-10 people. (We like to have a minimum of three volunteers at an aid station, irrespective of event size.) This group will present a unique and memorable mix of skills, experiences and personalities. You’ll get to know each other well.

You may be working under the guidance of an Aid Station Captain, who presents a unique knowledge of your assignment. A Captain, most likely, has years of experience at this particular event — if not this particular assignment — and should be your go-to person for questions and concerns. A Captain wants their volunteers to have a superb time.

Lastly, let’s not forget the runners. They will appreciate you and let you know it. They will shower you with smiles, thanks and heartfelt gratitude.

How will I know if I’m doing a “good” job?

A “good” volunteer has three overarching responsibilities: keep runners (1) safe, (2) moving and (3) happy. If you’re doing these things, you’re doing great. Let’s look at them one at a time.

Safe.

Here is the one of biggest take-aways of this guide: safety above all else. Race Directors want everyone associated with their events — runners, volunteers, spectators, passers-by, etc. — to be and feel safe.

Safety and satisfaction will inevitably lock horns on race day, and volunteers may be caught in the middle. Navigating this conflict should be easy, though, because we know who wins. Safety [in] first [place].

Let me give you an example. A few years back, at the Tahoe Rim Trail Endurance Runs, my friend — we’ll call him Jimbo — was among a handful of runners who were held back at an aid station due to lightning. Jimbo was running his first 50-miler and was right in line with his fairly ambitious goals. Sitting, however, in an aid station for some unknown period of time — Ten minutes? Two hours? — could dismantle all that. Jimbo pleaded with the volunteers to let him go. The chances of being struck by lightning, after all, are quite small. The volunteers rightfully held their ground and Jimbo added 30 minutes to finishing time. But he didn’t get struck by lightning.

It doesn’t happen very often, but there’s always a chance that a volunteer will have to go against a runner’s wishes in the name of safety. A runner will miss an aid station cut-off by 18 seconds, they’ll plead to go on, they’ll cry a gut-wrenching cry. But you’ll still pull them from the race. It’ll tear you up — but you’ll have done a good job.

Moving.

If a runner is safe, they should be moving as much as possible. Sounds obvious, right? I thought so, too, until I paced my good friend “Alice.”

Alice is the one of the most outgoing and shining people I know. She can strike up a conversation with anyone, at any time — including every volunteer, at every aid station. From a timing perspective, these impromptu conversations adds up. Four extra minutes at 15 different aid stations tacks on an hour to a runner’s finishing time. Of course, speed is not the only measure of success: Alice, for one, could care less how long it takes her to finish a 100. Her goal is to engage with the trail running community.

Unfortunately, Alice had to start caring about speed once the depths of night arrived. She was getting cold because she was spending too much time talking (read: being stationary) in aid stations. We needed to keep moving.

The aid station volunteers got it and gently nudged Alice along. My personal favorite: “Alice, I’d rather catch up with you over a beer at the finish line than over soup right here.” This volunteer didn’t get to spend three extra minutes with Alice, but they also didn’t contribute to Alice’s chill.

If a gentle nudge doesn't work, a volunteer should apply more force. “Get out of this aid station” is particularly effective. “Don’t sit down” works well, too. “Move" is crisp and actionable. It’s tough love, and it’s the hallmark of a good volunteer.

Happy.

Rounding out our podium of volunteer success measures is “happy.” We have no problem with it bringing up the rear because we view “happy” as an inevitable byproduct of the first two. A safe and mobile runner is a happy runner.

True, a runner might be grumpy at any given moment, but, deep down, they’re happy. You have to trust us on this. The runner’s joy will push to the surface once they’re across the finish line. If you'd rather not wait until the finish line to see a runner’s joy, here are a few things volunteers can do to bring it out earlier:

Smile

Tell a joke

Make eye contact

Ask a runner their name and use it

Tell them they look great (even if they don’t)

Tell them how impressed you are (because you will be)

We could add many more lines to this list, but you probably get the idea.

What will runners expect from volunteers?

Runners expect volunteers to help them achieve their goal. Simple enough. Volunteers do this by helping runners satisfy a handful of race-related needs, the majority of which are straightforward: “Hi, thanks for being out here — really appreciate it. May I have an orange slice, water refill and a hug?”

In reality, you won’t be able to meet a runner’s every need, however simple they may be. It’s altogether possible your aid station won’t have oranges. Instead, try to find a comparable solution: “I’m sorry, we don’t have any oranges. But we have plenty of fresh watermelon! Follow me.” Improvisation and empathy go a long way.

Before moving on, I’m going to offer a potentially discordant and counterintuitive view: Runners should not expect volunteers to be integral to the achievement of their goal. Let me try to explain. Conceptually, a runner should be able to complete an ultra-marathon without the help of volunteers. The runner’s training, strategizing and overall preparation should be more than enough to find the finish line — volunteers are just gravy. Granted, volunteers provide basic race infrastructure, like well-stocked aid stations, that create a bona fide event, but a runner should be able to cover the miles even if, hypothetically, the aid stations were unpersoned. The Plain 100 is a real-world example of this hypothetical state: Plain is an unmarked, unsupported, unpaced and uncrewed 100-miler on the rugged eastern slope of the Cascades. It’s tough but not impossible.

This perspective, however unusual, helps explain why runners do not expect volunteers to be knowledgeable runners themselves, let alone seasoned volunteers. Runners know and appreciate that volunteers are a wonderful “bonus.” If that wasn’t the case, we’d hear far more stories about runners getting upset with volunteers. In my 12 years of ultra-running, I have only seen a runner get upset with a volunteer on two occasions. As a community, we should be incredibly proud of this.

If you lend a runner a helping hand, even if you can’t meet their needs, you’ll have met their expectations.

It can’t be that simple. Won’t runners have questions?

Okay, you’re probably right. Runners will hit you with some event-specific questions. Here are the most common:

How far have I come?

This varies by aid station. Once you know which aid station you’ll be at, visit the race website for course information.

How far to the next aid station? How far to the finish?

Same as above.

What time is it?

This question can be interpreted in one of two ways: What time of day is it? How long have I been running? Either way, wear a watch!

What is the cutoff time?

Again, the race website is a great resource. Your aid station captain should know off the top of their head, too.

Do you have [insert specific item]?

A runner may ask, “Do you gummy bears?” While it would be great for volunteers to readily provide the answer to this type of question, it would also be magic. We cannot expect you to know every item in an aid station. Therefore, interpret this question as a request to help find a solution. In the above example, if you don’t know if your aid station has gummy bears, look for them — or find a close substitute, like starburst.

How am I doing?

“Wonderfully.”

So, what will I be doing?

To give you a concrete sense of what to expect, we detailed a few different volunteering roles. First, though, it’s worth pointing out that every volunteer should be prepared to wear multiple hats on race day. While unlikely, race conditions can deviate from plan, prompting changes in volunteer duties.

Marking the course.

What: Volunteers place some sort of temporary marking, typically construction ribbons/flags, along the course route. For simple sections of trial, this could be a ribbon every 0.10 mile. For more complex stretches, like a multi-trail junction, this could be an arrow sign. For overnight routes, course markings will be reflective and/or light-emitting.

When: Usually a day or two before the race.

Who: This role is typically reserved for volunteers who (1) are capable of covering longer distances on foot and (2) have an intimate knowledge of the course. It’s not uncommon for one volunteer to mark 10+ miles at a time. Markers should also be willing to strike up a conversation with a stranger. When hanging ribbons, a marker will likely encounter other users of the trail who are naturally curious about what’s going on. In this sense, the marker is also an ambassador for the event.

Where: Multiple points on the course.

Pro Tip: Bring a bigger backpack than you think. Although three-foot pieces of blue ribbon are small, 200 of these pieces take up a surprising amount of space.

Sweeping the course.

What: Sweeping isn’t quite as easy as it sounds. A sweeper effectively wears three separate hats. First and foremost, you have to motivate and encourage the runners who are just in front of you — the runners who are close to missing a cut-off. Second, you have to remove course markings and make sure they all get back to the RD. Ideally, these course markings can be reused. Third, you have to pick up any and all trash, whether it’s associated with the race or not. Our races adhere to Leave No Trace practices, which means we leave the trail better than we found it.

When: During and immediately after the race. Ideally, a sweeper crosses the finish line shortly after the race cut-off.

Who: A sweeper for a 50K may very well run the full 50K, albeit at a moderate pace. So, this volunteer should be fit. Equally important, this volunteer must be motivational and optimistic. A sweeper will be running just behind, if not directly alongside, runners who are flirting with the cut-off — runners who will appreciate positivity and encouragement. Lastly, a sweeper needs a discriminating eye. They cannot miss a single marking or piece of trash when they clean the course. The sweeper has to leave the trail better than we found it.

Where: Multiple points on the course.

Pro Tip: Bring goodies to share. I had the “joy” of spending an inordinate amount of time with a sweeper, and it made my day when they unveiled candy.

Recording finishers and times.

What: Logging a runner’s “official” finishing time is a relatively small but critical role. A large part of a runner’s lasting memory of an event may very well be their finishing time, so it’s important to get it right. Basically, an official race clock runs from start to end, and the volunteer records the precise moment that a runner crosses the finish line.

When: During and immediately after the race. You want to be situated near the finish line well before the first finisher is expected.

Who: Many races will have two people recording finishers to minimize the opportunity for error. And they can be just about anyone, as long as they’re willing to sit for a long period of time. For longer races, like a 100-miler, this could mean a 12-hour shift. It also helps to be, ah, assertive in social situations. Runners and other spectators will ask you about their time, their place, etc. — your focus is on the people finishing and you have to be willing to make that clear to these folks. You don’t want to miss a runner crossing the finish line because you were distracted.

Where: Finish line.

Pro Tip: Record everything twice. If, for example, a race is using an app-based timing system, it’s worthwhile writing down finishers and their times with ol’ fashion pen and paper. If one approach fails, you have a back-up. Plus, if a runner takes issue with their official time, race management can reference an additional data point when resolving discrepancies.

Checking runners in before the start.

What: Check-in processes range in time, complexity and requirements. I ran UTMB in 2016 and check-in lasted nearly two hours. The Plain 100M check-in, conversely, lasted a handshake. Wherever your event falls on this spectrum, check-in generally involves (1) confirming a runner’s identity and (2) giving them a race bib/number. In addition to their race bib, you may give runners a few other items — safety pins (to attach the race bib) and starter “swag” (like a shirt or buff) are common.

When: The vast majority of races have “morning of” check-in at the starting area. A few races, like most 100-milers, have “prior day” check-in. Some have both. It’s best to check a race’s schedule of events and confirm when and where you, as a volunteer, should be. Everlong, for example, occasionally offers prior day check-in at local running shops, in addition to morning of check-in.

Who: Anyone with a solid knowledge of the event. More on that under Pro Tip.

Where: “Morning of” check-ins are generally right by the start. “Prior day” check-ins may be somewhere else entirely. Either way, double-check the event website.

Pro Tip: Know the race well. Often, the check-in team is the first human point-of-contact between a runner and the event, so it’s likely they’ll receive a battery of race-related questions — “What electrolyte drink will you have on the course?”, What’s the finish line cut-off?”, “Do you allow early starts?” To play it safe, keep tabs on the RD for the more esoteric questions. (“If I run the full 25K course at 1:00am but am not back in time for the 7:00am ‘official’ start, can I start late — say, 8:00am? I really want to log 50K today.”*)

*If you’re at all curious, I’d probably respond, “Yes, you may. But you are still subject to the same cut-off times as everyone else. Haul ass, my friend.”

Directing traffic and parking cars.

What: Welcome to the unsung hero award. Your job is master a complex game of Tetris involving a finite number of parking spots and a seemingly infinite number of cars.

When: Arrive at least an hour before check-in begins. If a race starts at 7:00am and has check-in from 6:00am to 6:45am, be on site at 5:00am. This will give you plenty of time to confirm the number of available parking spots.

Who: This job is best performed by the assertive type. You are telling people where and how to park, and many will disobey you. It’s the truth. The most common infraction is the crew member who is “just dropping my runner off and leaving,” but then parks up front in a nonexistent spot. You have to make them move. Chances are you’ll work in a two-person team. One person to tell cars where to park, the other person to monitor how they actually park.

Where: At the parking area — which is not necessarily a parking lot — near the start. Races that start on public lands, for instance, may have limited side-by-side parking, so parallel parking along a dirt road becomes the parking lot.

Pro Tip: Ask the RD for a parking diagram/plan a week before the race. If they don’t have one, strongly encourage them to make one. You don’t want to be surprised by a lack of parking because you didn’t have an estimate of the number of cars and spaces. Parking is too often a problem and can sour a race’s reputation with other users of the trail and the local community. Also, wear bright and, if possible, reflective clothing and a headlamp. You want to be seen.

Checking runners in at an aid station.

What: At most races, volunteers record when runners (1) enter and (2) exit an aid station. This information serves two purposes. On the one hand, you can account for each runner and track their progress. On the other, we can share this status with a runner’s friends and family via web-based runner tracking tools. (We use UltraSignup’s runner tracking service.) To record a runner, you ask the runner for their number and double-check by looking at their race bib. Then, you crosswalk this number to a list of starters and record their enter and exit time. The record will look something like this: (37) John Doe, In: 3:46:30, Out: 3:47:52.

When: This job occurs throughout race day, from when first place enters the first aid station, until last place leaves the last aid station.

Who: Anyone with decent eyes and ears.

Where: Aid station(s).

Pro Tip: When a runner yells their number when they enter an aid station, yell it back. “Fifteen” and “fifty” are easy to swap, so it’s best to confirm.

Working at an aid station.

This is a big one. We estimate that 90% of volunteers are assigned to aid stations (versus, say, directing parking lot traffic). Therefore, we’re going to break this task down further — (1) runner care and (2) aid station maintenance — and address it outside of our “what-when-who-where” system. Instead, we’ll discuss these tasks chronologically.

(1) Runner care

When a runner enters an aid station, you should:

Step 1: Cheer. As soon as a runner approaches an aid station, tell them they’re doing a great job. Tell them they’re amazing. Tell them they’re made of pure sunshine. (You’re allowed to lie.). We want to inundate runners with positivity throughout the race.

Step 2: Get drop bag. If your aid station has drop bags, ask the runner if (a) they have a drop bag and (b) if they want it. Then get it. When they’re done with their drop bag, make sure it’s sealed up and put it in the “used” drop bag pile.

Step 3: Provide food and water. Most runners who come into an aid station will know exactly what they want and will go for it. Many, in fact, may not really need the help of volunteers. But many will also need help.

Step 4: Fill water bottles and/or hydration pack. It starts by offering to fill up their water bottles and/or hydration pack. Take these items from the runner, so they can focus on eating while you fill.

Step 5: Offer food. “What can I get you? We have [insert food item(s) here…]” Don’t be shy about effectively forcing or shaming a runner into eating. It’s amazing what a quick dose of glucose will do for the spirits!

Step 6: Offer care. In the midst of eating and drinking, runners may forget about tangential needs, like washing their hands or disposing of used gel wrappers. Ask them, “Is there anything else you need?”

Step 7: Kick them out! Do not let runners waste time. Unless they need medical attention or some other specialized care, they should not spend more than a few minutes in the aid station. Keep the runner moving.

(2) Aid station maintenance

When not tending to a runner, you should:

Task 1: Replenish food and water. Make sure food and water containers remain full. If you’re running low on a prepared item, like PB&J, make more of it.

Task 2: Clean. We’re not professional cleaners, but things should be organized and presentable.

Task 3: Stash trash. Keep an eye on the trash and recycling containers. We don’t want them to get too full or break.

Providing medical/first-aid.

We’re going to intentionally punt on medically-related roles. Many races have these positions filled before approaching the trail running community because they’re so specialized. What’s more, many permits require races to identify these positions beforehand. With our US Forest Service permits, for example, we have to identify a medical professional by name and credential

This should not discourage a volunteer from raising their hand for a medically-related role, however. As we said in the “How do I sign up” section of this guide, the more we know about you — the more you brag about your skills — the better. If we know that you’re an RN, we’ll find a way to draw on this incredibly valuable expertise. We keep an extensive first aid kit at every aid station, after all.

What should I bring?

This is one of the more challenging questions to answer because it’s so situation-specific. The gear you need to check in runners at the start is vastly different from the gear you need at Hope Pass in the Leadville 100. The former requires a list of runners. The latter requires 20 llamas. Instead of offering an itemized list of gear, we’ll share a few tips.

Ask ahead of time.

Once you’ve registered to volunteer, use whatever communication channel is available to ask what you should bring. Heck, feel free to ask us.

Bring more than you think you should.

With your recommended gear list in hand, it’s time to pack. We strongly encourage you to bring more than you think you should. Camping at altitude in sub-freezing conditions is markedly different from volunteering at altitude in sub-freezing conditions. You’ll be sleep-deprived and more susceptible to the cold. You’ll want that extra layer (or two).

Who knows? You might make a new best friend because you brought that extra turkey sandwich.

Know the wilderness basics.

Very few trail races occur in backcountry or wilderness areas because of permitting limitations. (Which is a good thing, in our view.) Nevertheless, it’s important to know and bring the “ten essentials” for volunteering assignments near wilderness or backcountry.

Gary Robbins, one of the most accomplished and authentic ambassadors of trail running, assembled a 15-minute video, The Ten Essentials for Safe Backcountry Adventures, that we highly recommend. Gary details the ten essentials as well as a “few extras” that he (and we) recommend. The video is tailored for runners, but the lessons can be broadly applied.

How do I setup an aid station?

Setting up an aid station should take two to three people about 30 minutes. Unless you’re a seasoned volunteer or an aid station Captain, you will rarely do this alone. Aside from being tedious, setup involves certain tasks, like unfolding the 8’ x 8’ canopy, that are a lot easier with multiple people.

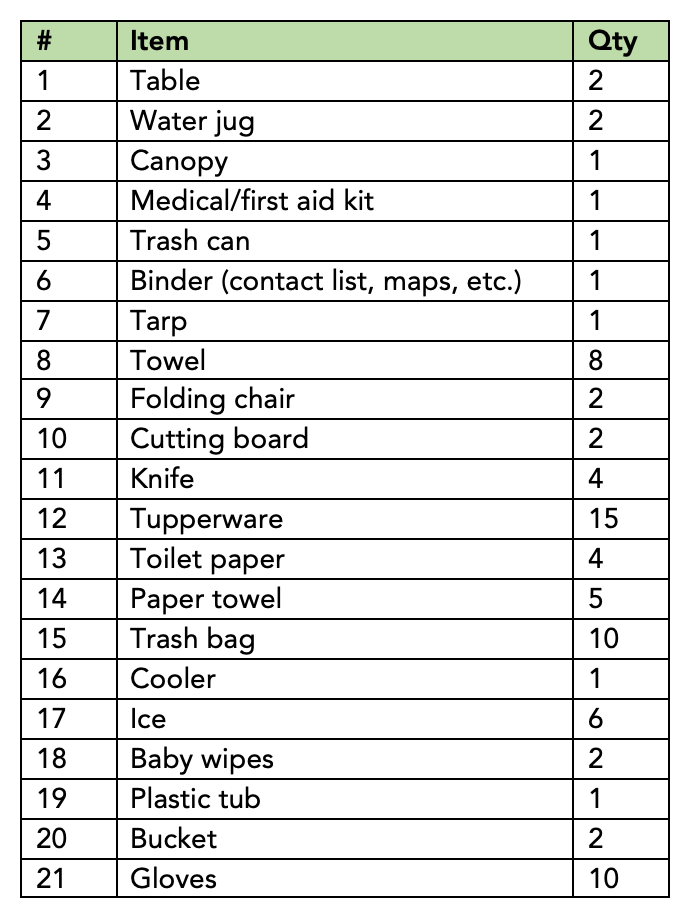

Below is a step-by-step process that we share with our volunteers and keep in our aid station binders. The items in BOLD (#) correspond to our gear list, which you’ll see in the subsequent section, “What will be provided?” If a step seems missing or suboptimal, feel free to improvise and adapt to conditions on the ground.

This picture should provide a sense of an aid station’s overall footprint.

Unfold TABLES (#1) and set them end-to-end lengthwise. Remember to lock the legs!

Place WATER JUGS (#2) side-by-side on one end of the tables. The jugs should be readily accessible. Fill one jug with water and one with electrolyte drink. In the aid station binder are “Water” and “Electrolyte” signs that you should tape to the coolers so runners can tell the difference. Keep the coolers full all day.

Open CANOPY (#3) and place over the tables. The tables should be at the front of the canopy, relative to where runners will approach. The canopy will not cover both tables, so leave the end with the water jugs exposed.

Place FOLDING CHAIRS (#9) next to — but not under — the canopy. If possible, place the chairs in the shade. The chairs are for runners.

Lay TARP (#7) next to canopy, on end opposite water jugs. The tarp is for placing items, like drop bags, on the ground without touching the ground. Runners may also want to sit on it, which is fine.

Place MEDICAL KIT (#4) on the table.

Remove the following items from the medical kit and place them on the table, so they’re clearly visible to runners: (a) bug spray, (b) salt pills — e.g., Succeed S! Caps, (c) hand sanitizer, (d) Vaseline, (e) Tums, (f) BABY WIPES (#18), (g) TOILET PAPER (#13) and (h) PAPER TOWELS (#14)

Tie a TRASH BAG (#15) to the leg of the canopy so it’s secure and visible to runners. The bag should be tied to the canopy leg that’s closest to the “exit” side of the aid station.

Place the TRASH CAN (#5) against or near an upright structure — for example, a tree — about 30 feet down the “exit” side of the trail. Put a TRASH BAG (#15) in it, please. This trash can is for runners who are eating and moving toward the aid station exit.

Place the PLASTIC TUB (#19) at the back of the canopy, away from the tables and runners. This will be a makeshift table for the volunteers. Place the TOWELS (#8) and BINDER (#6) on it. The towels are for messes and the binder is for volunteer information.

Place the COOLER (#16) at the back of the canopy as well, next to the plastic tub. The cooler will be for perishable foods and ICE (#17) — so try to keep runners out of it. The ice in the cooler is for consumption. Offer it to runners when filling their water bottles and/or hydration packs.

Fill the BUCKETS (#20) about halfway with ICE (#17) for runners to grab for cooling their bodies — not for consumption. Add TOWELS (#8) to the buckets as well, and make sure the ice doesn’t melt too fast. Place the buckets on the ground next to the chairs, preferably in shade.

Spread the TUPPERWARE (#12) on the aid station table and fill each container with a different food item. Importantly, we only want one food item per container. Group similar foods together — salty, sweet, protein, etc. One table should be devoted to food, while the second table should have at least 2/3 covered in beverages

Put the CUTTING BOARD (#10) and KNIFE (#11) wherever you want, as long as they stay out of the runners’ way. You’ll use these items throughout the day — cutting oranges, spreading peanut butter, etc.

What will be provided?

The answer to this question will, like many things we’ve discussed, depend on the specific race. In general, though, you should be given everything you need to successfully do your assigned job. To give you a clearer sense, here is an abbreviated look at our “basic” equipment list for an aid station. The full list would take up way too much room.

If, in the course of your duties, you think something is missing, just ask. There’s a decent chance it’s hidden or in the wrong place. Because aid stations have so many things, it’s possible to lose track or one or two.

What happens when my shift is complete?

This may not be as easy as it sounds. Ultra-marathons have a long history of not going according to plan for runners, and this extends to volunteers as well. How, then, does a volunteer gracefully exit stage left?

Start with a clear timeline and end with a status report.

Clear timeline.

All parties involved want to minimize surprises and mistakes. Therefore, we publish schedules for each of our aid stations:

This schedule gives us and our volunteers a starting point. I emphasize starting point because, again, reality can deviate from plan. I’ve experienced plenty of eight-hour volunteer shifts that seamlessly morph into ten-hour volunteer shifts. Be prepared for some “slip.”

Of course, you don’t have to extend your volunteer shift nor feel guilty for not doing so. Perhaps you have a hard stop at a particular time. Perhaps your ability to contribute drops precipitously at a certain point. No matter the reason, all you have to do is speak up — early and often. At Deschutes River in 2018, we had two excellent volunteers who let us know beforehand that they had a hard stop at 2:00pm. We welcomed this additional information and planned accordingly.

Status report.

When it is time for you to hit the road, make sure you deliver a status report to the appropriate person(s). We’re not talking about a written deliverable here — more like a three-minute conversation. You’ll want to cover what you accomplished, what’s left to be done, and anything else that’s worthy of someone else’s attention.

Your status report also ensures that people know you left. If you depart unannounced, your absence will be noticed and may cause concern — concern, mind you, not for the event but for you. Race Directors want to know everyone made it home safe.

How do I break down an aid station?

Thanks for staying after the runners! Rest assured, we want to get you off the course as quickly as soon as possible. Therefore, we assembled these aid station breakdown instructions that balance (1) duration and (2) order. Don’t go too fast, though. Breaking down an aid station has one non-negotiable: we leave the course spotless.

Breakdown equipment and store food.

Breaking down the aid station is simple: go backwards through the setup process. Don’t feel compelled to clean anything or put food back in its original containers. Keeping it in Tupperware is fine. Place perishable food in the cooler. With that said, use your judgment when it comes to keeping perishable food that is past its prime. We don’t want to waste, but we also don’t want stale PB&Js for breakfast.

Put equipment in vehicle.

Once all your equipment is packed up, please put everything in your designated breakdown vehicle. We’ll unpack the vehicle at the start/finish.

Clean entire area.

It’s critical we leave no trash or, for that matter, any sign that a trail running event took place. Best case, someone could walk through the aid station area an hour later and find it better than we found it upon our arrival. By “entire area,” we mean the immediate aid station footprint and 30-40 feet in every direction. Also, you should walk up and down the trail about 100 yards in both directions to look for anything a runner may have dropped while trying to eat quickly.

Just in case it doesn’t go without say, volunteers should collect everything that’s not supposed to be on the trail, even if they know the event wasn’t responsible. We leave no trace.